April 1863

WORKING MEN’S HOUSES AT STOCKBRIDGE.

Last night, the foundation-stone of a range of houses at Stockbridge, intended for working men, was laid by Dr Begg, in presence of a considerable number of spectators.[1]

It will be remembered that about eighteen months ago Dr Begg inaugurated, by the same ceremony, the commencement of the erection of another row of houses for a similar purpose at the west end of Water Lane,[2] leading from Canonmills to Stockbridge.

The houses run along the bank of the Water of Leith, and are named Reid Terrace. They consist of two storeys—the entrance to the lower being on the east side; to the upper, on the west side, by broad and high flights of steps.

The accommodation in the case of all is complete; each house is self-contained in every respect, and nothing is wanting to the comfort of the tenants. The accommodation in the tenements on the ground-floor consists of a kitchen and two rooms—that of the upper flat, of two rooms, a kitchen, and two attics. Every house is provided with a piece of garden ground, in front or behind, according to its position in the building.

The rent of each house on the ground flat is £11, that of each on the second flat £13.[3] All the houses have, however, been sold to the tenants by an arrangement with the Property Investment Company. The greater number of them are finished and occupied—the others are at present in course of completion.

The range of houses of which the foundation-stone was laid last night is intended also to be occupied by working men, and to complete the street, of which Reid Terrace forms the western side, and which will run nearly north and south, forming a chord to the arc which the river describes.

The new houses are to be precisely similar in appearance, in accommodation, in completeness, and in price. This side of the street, however, is intended to be named “Hugh Miller Place.” There will be 32 houses, containing 64 tenements, and of these a considerable number are already sold.

The proceedings last night were opened with a prayer by the Rev. Mr Muir.

A bottle containing specimens of the current coins, newspapers, &c. &c., was placed in the cavity of the stone, which was then laid by Dr Begg in the usual manner.

Dr Begg said it was with the greatest satisfaction he was here this evening, to lay the second foundation-stone in connection with this Co-operative Building Society. He rather thought that when, eighteen months ago, he laid the former foundation, there were some who supposed it would be the last stone of the kind that would be laid in Edinburgh. He saw a good many shakings of heads even on the part of some of his own excellent friends; but he was sure, after seeing that beautiful row of houses behind, and finding that the Society were proceeding with two new rows of buildings to-night, even the most incredulous would be persuaded that the working men of Edinburgh were able and determined to solve this great problem in regard to houses.

There was no doubt that the question of houses for the working classes was the most important social question in Scotland. The fact was brought out some time ago, on the most authentic possible information, that 1,000,000 of the people of Scotland, or one-third of the whole population of the kingdom, were occupying houses of only one apartment.

When he mentioned that the Parliamentary Committee stated, in reference to houses of only one apartment, that it might be assumed that they were unfit for the habitation of human beings, they could easily understand what the social state of Scotland must be when one-third of her whole people were occupying these one roomed houses.

The city of Edinburgh was no exception to the general rule. About 50,000 of the people of this city were living in houses of one room; 121 of these houses had no windows, and upwards of 1500 of them had from six to fifteen human beings residing in them.

Now, he would appeal to any man of the least consideration what the social state of many of the people must be in such circumstances. How was it possible for the decencies and comforts of human life to be observed in such circumstances?

He was persuaded that till the statesmen of this country awoke to a consideration of the importance of this question no real social progress could be made. It was vain to spend thousands upon thousands upon pauperism; our pauperism now cost about £700,000 a year. It was far worse than vain to make palaces for the residence of our criminals when the question how working men were housed never seemed to occupy one moment’s time in the Parliament of our country. Until that question was duly faced and considered, he would repeat no social progress could reasonably be expected; but, then, if working men waited till Parliament did it, he had always been persuaded that they would wait long enough—(laughter, and “Hear, hear”)—and therefore he rejoiced that they had begun to do it themselves, and to do it in the best possible way.

It was now twelve years since he published an address with this title, “How every man may become his own Landlord;” and in that address he expounded the very principles which were being acted out in connection with this Building Society at present.

In the first place, it seemed to be essential that a working man should have a self-contained house. He had no idea that a working man was not as much entitled and as much bound to look out for a self-contained house as any other man, and they could easily understand that where a man lived in a common stair, for example, it was impossible for him to be accountable for all that were living in that stair, and one black sheep in the stair could destroy the comfort of all the people that lived in it; but then when a man had a self-contained house, he knew where the blame rested, and whether his wife was to blame. It concentrated the responsibility, and gave people an opportunity of being comfortable and cleanly, if so disposed.

Therefore, he said, in building self-contained houses, as the Society had done, and were now intending to do, they were building the best possible kind of houses for working men as well as for other men. Then, again, they were doing it themselves. He had always scouted[6] the idea that working men required to have the spoon held to their mouths, as if they were children—requiring to be patted on the back, and patronised, as if unable to do anything themselves; whereas, in point of fact, the whole floating capital of the country was passing periodically through the hands of working men, and all that was required was that they should learn to economise, and co-operate, and manage their own affairs with discretion.

Then there was no reason at all why they should not only have houses of their own, but why they should not climb even to the highest step of the social ladder. The way in which that object was accomplished in connection with the present Society was very simple. Any man that had £5 could now get a house of his own. They might come and buy one of these houses if they could table down £5, because the Property Investment Companies advance the rest.

On a house on the ground floor, having two rooms and a kitchen, which cost £130, the Property Investment Companies would advance £125 upon the security of the house.[7] Well, then, if they wanted to rent one of these houses they would pay £11 a year rent, whereas what the Property Investment Company would charge was just £2 more—£13 a year, and that only for fourteen years, at the end of which time the house would become the property of the tenant and would belong.to his children after him—(applause).

Well, then, take a house above, containing two attics, in addition to two rooms and a kitchen. The house cost £150. Suppose that a working man was disposed to buy one of these houses, and that he required to borrow an additional £25 from an Investment Company. For that he would require to pay £2, 12s. a year; in other words, a rent of £15, 12s. a year. The rent of these houses was £13 a year, and thus by paying £2, 12s. a year he would become in fourteen years the owner of the house.

He was persuaded that as the simplicity of the system was understood, they would have a great extension of these working men’s houses in Edinburgh—their own property; and that he took to be the effectual way to under-prop the whole social fabric, and give to every man a stake in the property of the country.

There were two difficulties no doubt in the way, but one of these had been thoroughly overcome. One difficulty was the titles. They had had the greatest possible puzzling, and had still in some districts, with their legal friends obliging them to have to do with whole bales of old parchments at very great expense. That had been all simplified; an arrangement had been made by which titles could be procured at a very small expense indeed. The other difficulty was the ground. They were obtaining ground here, but this ground would not last them long. He expected soon to see every foot occupied, and the question was where to go next.

His answer was—go to the Governors of Heriot’s Hospital, go to the Magistrates, the Council, and the clergy of the city, and tell them what vast and extensive ranges of land they had. They had 33 acres stretching from Leith Walk round to St Mary’s Church unrestricted, yielding the Hospital at present only £10 a year.[8] The working men should tell them that they would give double that sum, and ask them in the name of the best interests of the city of Edinburgh to feu it to them—not to lock up the land in the city like the dog in the manger, but to put the land within the reach of the people of Edinburgh, that they may have ground on which to erect houses.

That matter seemed to him of the utmost importance; and, therefore, he had taken the liberty in connection with this Co-operative Society to offer two prizes—one of £5, and another of £2—and the Society offered one of £3, for the three best essays on working men’s houses. Now he left the matter in the hands of the working men, and he was persuaded it was in good hands. He was persuaded that Edinburgh had awakened to life in this important enterprise, and hoped that out of Edinburgh an intelligence and spirit would proceed which would have a good effect on Scotland.

Our English friends had been proceeding with this matter for many years, and he heard they were proceeding with unabated vigour. His friend Mr Taylor of Birmingham sent him a paper a few days ago, and he said the Association in the town had been most successful. They were buying up all the land around Birmingham, and there were now hundreds of delightful working men’s houses all round the town. Let Scotland also show an example, let her do justice to her own intelligence. If Lord Palmerston should come to see them again,[7] the working men would have no difficulty in selecting a topic on which to address him. They could bring him down and show him these houses, and they could tell him that Scotland was equal to the task of curing her own social evils, and that she was in the way of effectually curing them by the building of comfortable houses for the people.[8]

Mr Kemp, the Chairman of the Property Investment Company, in proposing a vote of thanks to Dr Begg, paid a high compliment to his exertions in the cause of the working classes, as shown in his endeavours to improve the bothy system and to provide suitable accommodation for the working classes.

With reference to Reid Terrace, Mr Kemp stated that, notwithstanding the predictions of the master builders, by last November 350 shares in that row of houses had been taken up, and the result was that they were now completed; and what was better, they were all sold; and better still, they were all paid for—(cheers)—at least the money was all ready for the Treasurer of the Institution.

With regard to the other operations of the Society, he had to state that in Leith they had taken a large field, on which they were laying down 44 houses. They never grudged to give good wages to their workmen last summer, they had retained their labourers in the harvest season, they dealt with all liberally, and the result was that they had in their employment the best working men in Edinburgh—(applause).

A cordial vote of thanks was then given to Dr Begg, and the proceedings terminated.

Caledonian Mercury, 7 April 1863

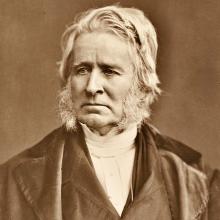

[Image top-right of James Begg by John Moffat, Wikipedia, creative commons.]

[1] The Edinburgh Cooperative Building Society was established in 1861 by stonemasons following the ideas of 3 Free Kirk luminaries—Hugh Miller (1802–56), stonemason, geologist, writer, editor of The Witness; Dr James Begg (1808–83), minister and writer; Hugh Gilzean Reid (1836–1911), journalist, editor of the Edinburgh Weekly News, Liberal MP from 1885 to 1886.

[2] Water Lane was renamed Glenogle Rd in 1875.

[3] About £650–770 today, or 55–65 DWST, 1863.

[4] The word ‘scouted’ appears in the original, but is perhaps a typo for ‘doubted’ of ‘scorned’.

[5] A security worth about £295 and an advance of about £7,400 today, or 25 and 625 days’ wages for a skilled tradesman in 1863.

[6] Presumably, St Mary’s, Bellevue Cres.

[7] Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784–1865) was a Liberal MP and Prime Minister (1855–58, 1859–65). At the invitation of the city’s Liberal Committee, he visited Edinburgh and Leith during the Easter recess of Parliament in early April 1863.

[8] By 1911, the Edinburgh Co-operative Building Society had constructed over 2,000 houses on 11 sites across the capital.