WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE TO TRANSFORM A LIFE?

What’s the best thing you’ve done lately for a complete stranger?

Given up a seat on the bus? Helped someone across the road? Dropped a few coins in a hat?

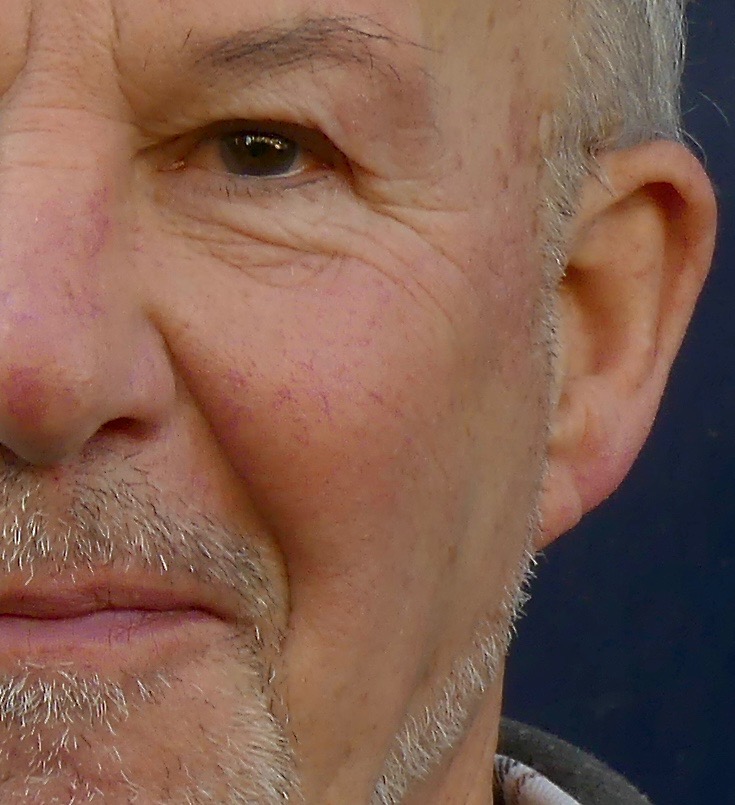

They’re all admirable in their way, but they rather pale into insignificance compared to a contribution made by local resident Richard de Soldenhoff last year.

Back in November, he donated a kidney to someone he doesn’t know, has never met, and has no expectation of meeting in future. It was purely and simply a life-transforming gift.

Richard is a 69-year-old retired medical doctor. He trained first as a GP in Edinburgh, but then spent most of his career tackling the curable scourge of leprosy in locations such as Zambia, the New Hebrides, Tanzania, Nepal, India, Nigeria and latterly Indonesia.

Since his return nine years ago, he’s volunteered as a care-assistant for disabled holidaymakers and as a sighted guide for the blind. But he was inspired to take caring to the next level by the example of an old school friend, whose enjoyment of life – drastically restricted by chronic nephritis – was restored after a successful organ transplant.

Richard was keen to make a difference like that himself, and after reading an article in the Guardian and turning the matter over for several weeks, resolved to offer himself as a donor.

In the UK there are 6,000 people on the waiting list for a kidney transplant, over 400 of them in Scotland. Each year, 300 die of kidney failure before receiving a new organ.

‘Non-directed’ living donors like Richard make a huge difference. They’re not related to the recipient, and so add significantly to the pool of people with an interest and capacity to help.

Another benefit is found in the long-term outcomes. Because the surgery is carefully scheduled, any delay between removal and insertion is minimised. As a result, the chances of success are greatly improved: 90–95% of recipients from living donors are themseves living healthily one year after their operation.

Richard found the whole process straightforward. First, there were interviews with a psychologist to make sure he was clear-minded and non-whimsical about wanting to take part. More talks followed with officials from the Human Tissue Authority to ensure he was not being coerced or paid. Then there were careful briefings on exactly what was involved, and plenty of blame-free opportunities to change his mind.

Finally, of course, there were exhaustive medical checks. Age isn’t a barrier (the youngest live donor in Edinburgh was 27, the oldest 83), but you have to be fit. In most volunteers’ cases, it takes about 9 months from first contact to surgery.

Being of a sceptical bent, mean-minded and timorous, this correspondent had a few questions.

‘On the fitness thing,’ I said, asking for a friend, ‘would someone who led, say, a reasonably dissolute life still be eligible to donate?’

‘There are very careful medical checks. This is the full service, not an MOT. And if necessary, they will help you to become fit.’

No way out there, then.

I began mentally filling my diary with as many vital appointments as possible.

‘How long does it take to recover from giving a kidney?’

Richard surveyed what pass for my broad shoulders, honed torso and rippling biceps.

‘Most people are back to normal after 6–8 weeks,’ he said, ‘after which there’s no impact. I went up a hill after 3½ weeks, and was on top of a Munro in the snow after 2 months.’

I decided to baffle him with science.

‘Why has Nature given us two kidneys if we need only one?’

Richard fixed me with a kindly but quizzical expression suggesting he thought I had no medical qualifications and couldn’t remember even the basics of O-level Biology.

‘One kidney is a spare,’ he replied. ‘You don’t need the other.’

‘But what if the one you’ve got left goes wrong?’ I pounced. At last, I felt I had devilled him.

‘It should last you for life, particularly because the screening process is designed to select only healthy people with 100% efficient kidneys. Put it this way: It’s a lot less risky than scuba diving, or cycling in Edinburgh.’

I had no answer to that either, and have not thought of one since.

In fact (cowardice, selfishness and lethargy aside), I can think of no good reasons for not joining the 52 other people who have made non-directed kidney donations in Scotland since 2007.

They’re not saints, Richard points out, ‘just ordinary people, fit, with some spare time and a wish to do something useful to meet a huge need’.

In all seriousness, it’s clearly a viable option for many people wanting to make a difference, and one well worth considering.—AM

To find out more about non-directed kidney donation, visit the Give a Kidney charity here or Organ Donation Scotland here.